*Disclaimer: At the time of writing this, Wireguard is not in stable repositories of some distribution. *

**Secure Shell (SSH) **is a useful utility which allows administrators to remotely control a plethora of devices ranging from routers to UNIX servers without exposing credentials in plaintext. Today, the majority of LINUX and UNIX based systems run a implementation of SSH called OpenSSH. Developed by the talented people over at the OpenBSD project, their implementation of SSH is completely opensource and free to the public.

On the contrary, Wireguard is a recently released communication protocol which is incredibly lightweight and simple. By working with purely key-based authentication, we can deploy hosts within seconds without any hassle of port forwarding on the client. As a result of this, people stuck behind a CG-NET deployment or even an IPv6 only network can tunnel without being concerned with opening ports.

By combining the two technologies, we can create a Virtual Private Network (VPN) by which the SSH service is exposed on, but not the WAN. By doing this, it drastically reduces the attack surface of SSH. I suspect this way of authentication is more useful for high security zones such as a co-location facility, however, there’s no harm in securing your own infrastructure… right?

Outlining how a Jump host functions

SSH utilises the jumper node as a intermediary for traffic A jump host will act as a intermediary between yourself and the target machine. You may jump more then once, but in this example there will only be 1 added hop. Ordinarily the user would not be able to access the nodes, however, by utilizing the Jump node as a intermediary we can then SSH into a node on the VPN.

SSH utilises the jumper node as a intermediary for traffic A jump host will act as a intermediary between yourself and the target machine. You may jump more then once, but in this example there will only be 1 added hop. Ordinarily the user would not be able to access the nodes, however, by utilizing the Jump node as a intermediary we can then SSH into a node on the VPN.

Installing Wireguard

With the release of Wireguard into the Linux kernel 5.6, I would like to consider it a stable piece of software. In fact, with the addition of it in stable distributions such as Debian 11 it may even be classed as so. However, common stable distributions may lack behind the new 5.10 LTS kernel which means an equivalent of back ports has to be used.

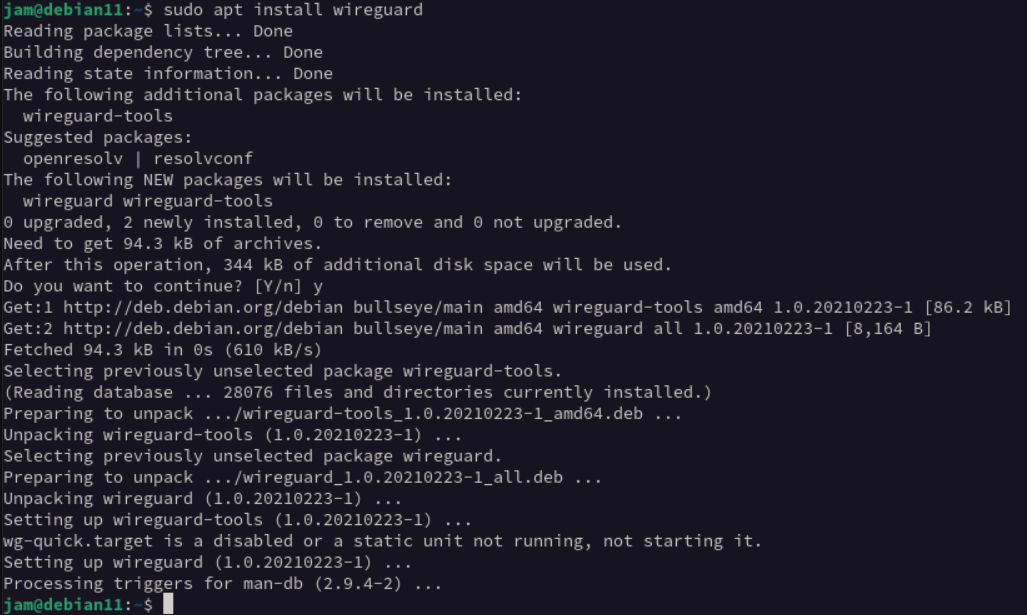

Debian 11 ‘Bullseye’

As mentioned, Debian 11 runs the latest 5.10 LTS kernel which means it has native support for Wireguard. As such, installing it is simple:

sudo apt install wireguard

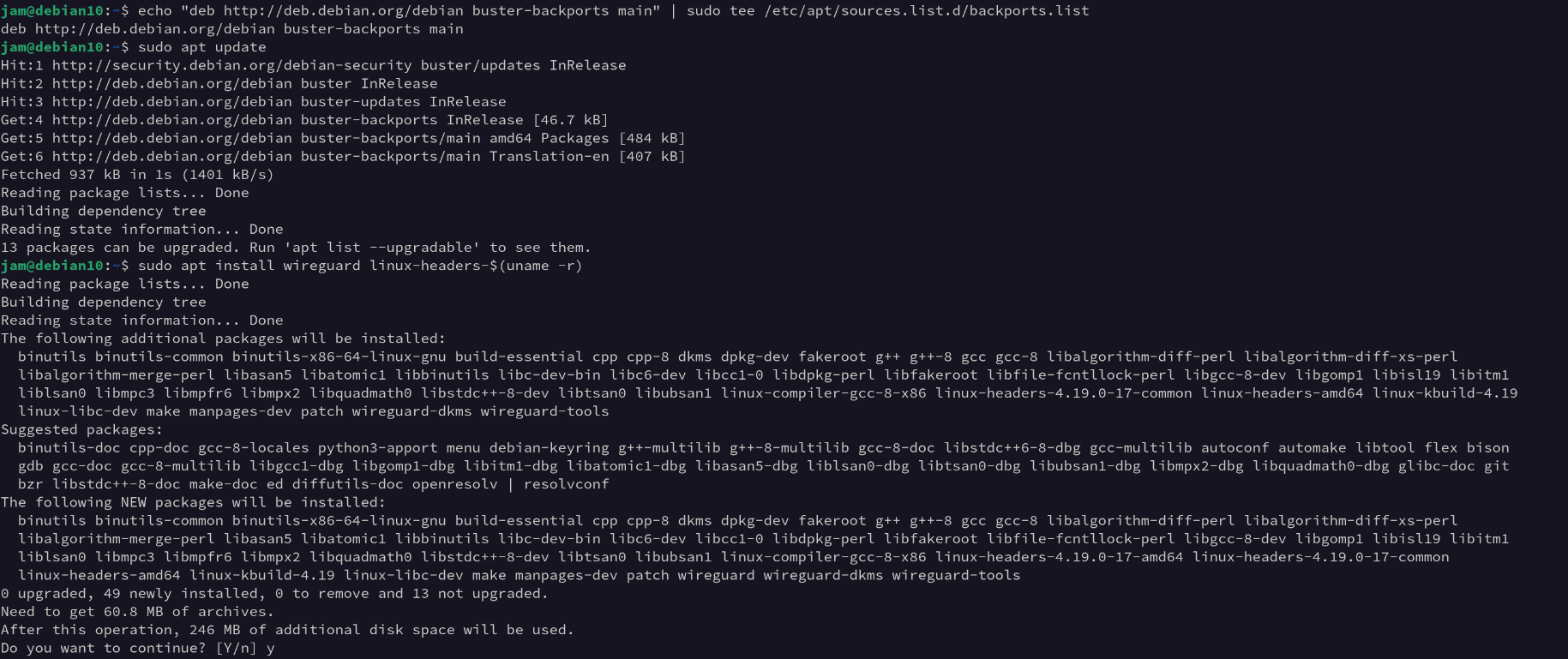

Debian 10 ‘Buster’

A little more complex, requires us to install the back ports repository and Linux headers. To do this, we must create a entry in /etc/apt/sources.list.d containing the repository.

echo "deb http://deb.debian.org/debian buster-backports main" | sudo tee /etc/apt/sources.list.d/backports.list

Then we need to update our information for package sources:

sudo apt update

And finally followed by the install.

sudo apt install wireguard linux-headers-$(uname -r)

When I was installing this on some of my routers, I noticed that I could not find the correct linux-headers package. In my case, this was because I had previously updated my kernel without rebooting.

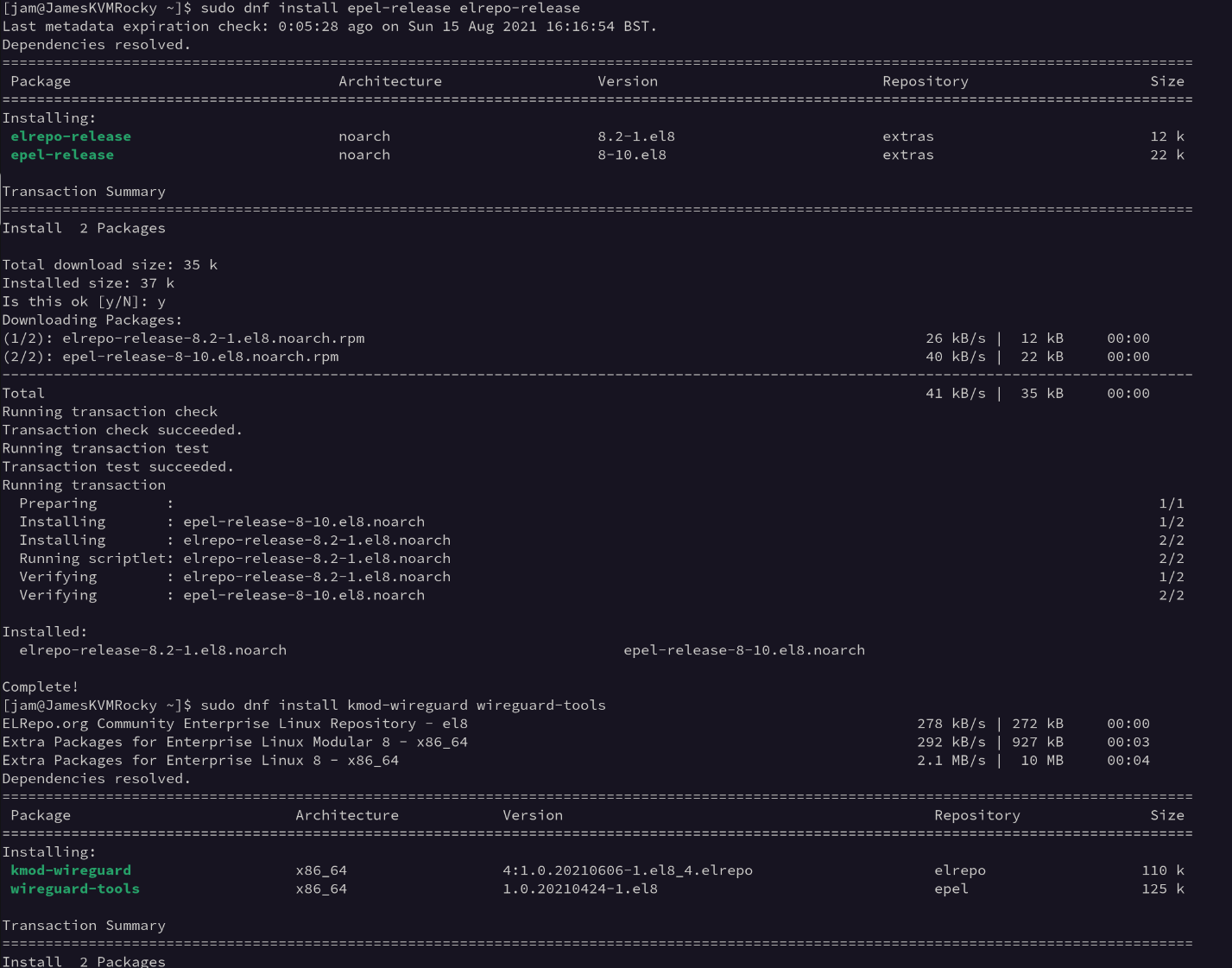

Rocky Linux 8.4 ‘Green Obsidian’

Similar to Debian 10, Wireguard is not present in the base repository list nor Linux kernel until a new release comes out on the 5.10 LTS kernel. So for now, we must install both the epel-release and elrepo-release repositories.

sudo dnf install epel-release elrepo-release

I was happy to read that the epel-release repository was maintained by the Fedora team. However, the elrepo repository appears to be entirely third party.

Next, we just have to install the packages:

sudo dnf install kmod-wireguard wireguard-tools

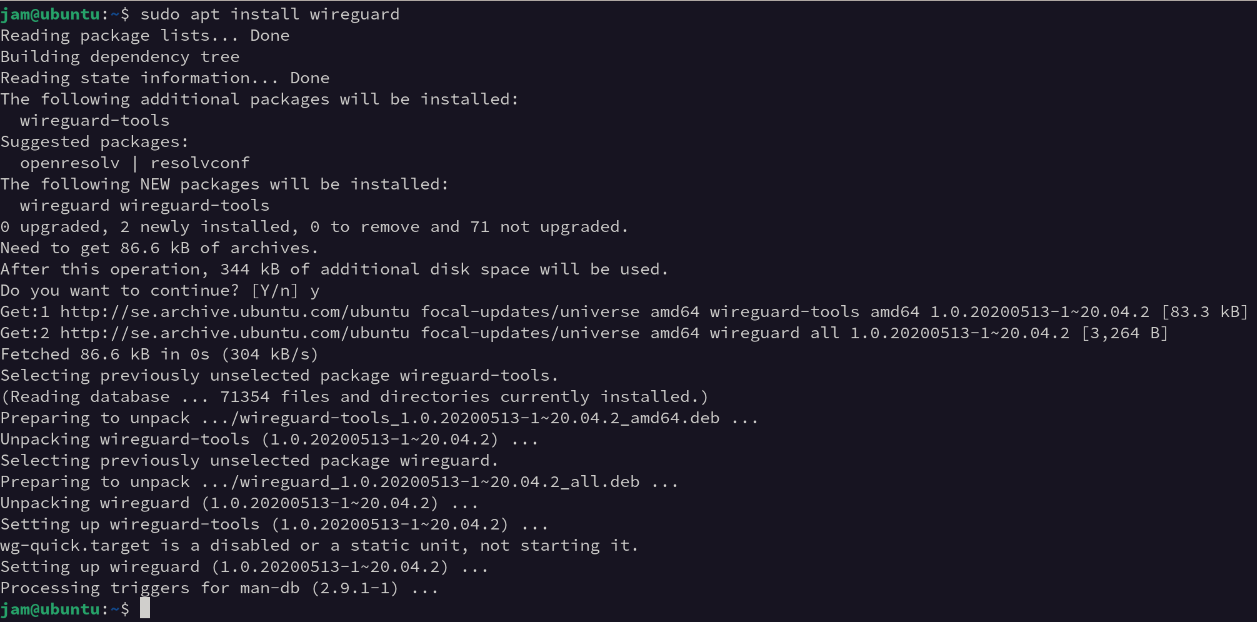

Ubuntu Server 20.04 LTS ‘Focal Fossa’

While I’m not an Ubuntu person, I am sometimes jealous of the up to date package repositories… Similar to Debian 11, we just have to install the wireguard package.

sudo apt install wireguard  —

—

Configuring Wireguard

Wireguard uses a public key authentication system. This means that each side of the tunnel has a store of keys to encrypt traffic with that only the correct peer may decrypt.  Each peer communicate in a secure manner by encrypting it’s traffic with the peer’s public key Comical drawing aside, the above illustration displays a abstracted view of the transaction. Do not that this transaction will happen on both sides, it is not a client-server model.

Each peer communicate in a secure manner by encrypting it’s traffic with the peer’s public key Comical drawing aside, the above illustration displays a abstracted view of the transaction. Do not that this transaction will happen on both sides, it is not a client-server model.

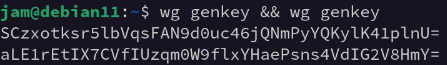

On both the Jumper and the endpoint, we need to generate a private key. This will create a public key based off it which we will need to take note of. This can be accomplished with the command:

wg genkey  You’ll need to do this command twice, and take note of the keys generated.

You’ll need to do this command twice, and take note of the keys generated.

Once we have the keys, we can go ahead and configure our Wireguard configuration files. By default, Wireguard will read from the /etc/wireguard directory. In here, we want to create a file called wg0.conf and configure our tunnel.

sudo nano /etc/wireguard/wg0.conf

Jumper

Some things to note about the configuration of Wireguard is that it fully supports dual stack networking. As such, not only can your VPN have IPv6 but it can also tunnel over IPv6! Just ensure you encapsulate the endpoint variable in [] if you plan to use IPv6. In anycase, here is my configuration file:

1

2

3

4

[Interface]

PrivateKey = 4IUXksWM2WyPWr3jAmmbRDxLNdDTDKTiOfIr1pLhaEg=

Address = 10.40.0.1/24

ListenPort = 12342

Example configuration file Then we can bring up the interface and view the public key it created. We will need to note this down as it’s required for our endpoint to encrypt traffic with.

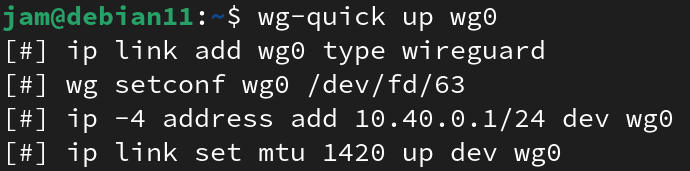

wg-quick up wg0

We can see that we received a basic verbose output stating what commands have been executed:  It will execute commands for us to create the interface Now we can retreive the public key of this configuration file. Actually, the command will show us more information then this but as of right now it’s only useful for this,

It will execute commands for us to create the interface Now we can retreive the public key of this configuration file. Actually, the command will show us more information then this but as of right now it’s only useful for this,

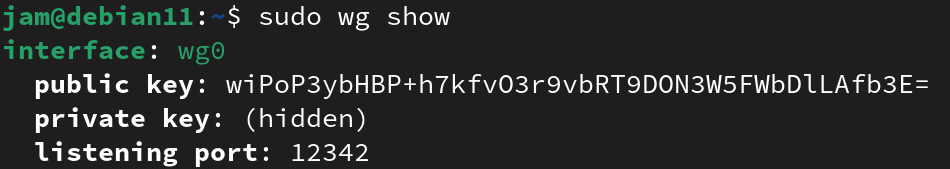

sudo wg show  The command will output the public key and other helpful information Once we have this public key, we are ready to configure the endpoint.

The command will output the public key and other helpful information Once we have this public key, we are ready to configure the endpoint.

Endpoint

Similar to before, we need to edit /etc/wireguard/wg0.conf but this time we have the addition of a peer notation thanks to the public key we generated above.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

[Interface]

PrivateKey = 0HGqP0XNeXz3AWOniHwkNeBXQIsMiajiHl5+5uyBilA=

Address = 10.40.0.2/24

ListenPort = 12342

[Peer]

PublicKey = wiPoP3ybHBP+h7kfvO3r9vbRT9DON3W5FWbDlLAfb3E=

AllowedIPs = 10.40.0.1/32

Endpoint = 10.10.69.54:12342

PersistentKeepalive = 20

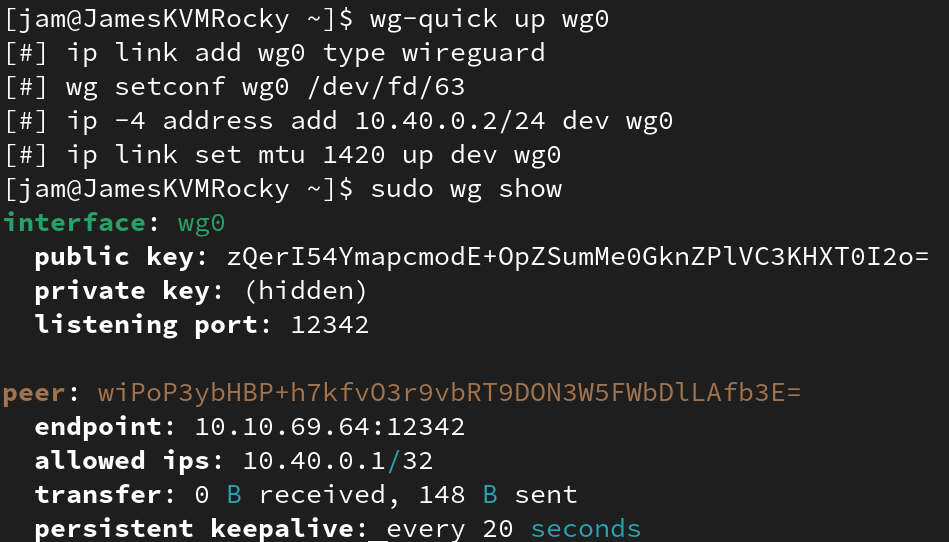

Example configuration file in addition to peer After bringing up the interface, we can see not only the interface configuration but a peer configuration!  Full configuration for the endpoint Once more, we need to log the public key and adjust our Jump config.

Full configuration for the endpoint Once more, we need to log the public key and adjust our Jump config.

Jumper

Go ahead and replicate the peer configuration we created on the endpoint, exchanging the appropriate variables:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

[Interface]

PrivateKey = 4IUXksWM2WyPWr3jAmmbRDxLNdDTDKTiOfIr1pLhaEg=

Address = 10.40.0.1/24

ListenPort = 12342

[Peer]

PublicKey = zQerI54YmapcmodE+OpZSumMe0GknZPlVC3KHXT0I2o=

AllowedIPs = 10.40.0.2/32

Endpoint = 10.10.69.30:12342

PersistentKeepalive = 20

However, we can’t “up” and already active interface so we must down it then up it to make the changes take effect.

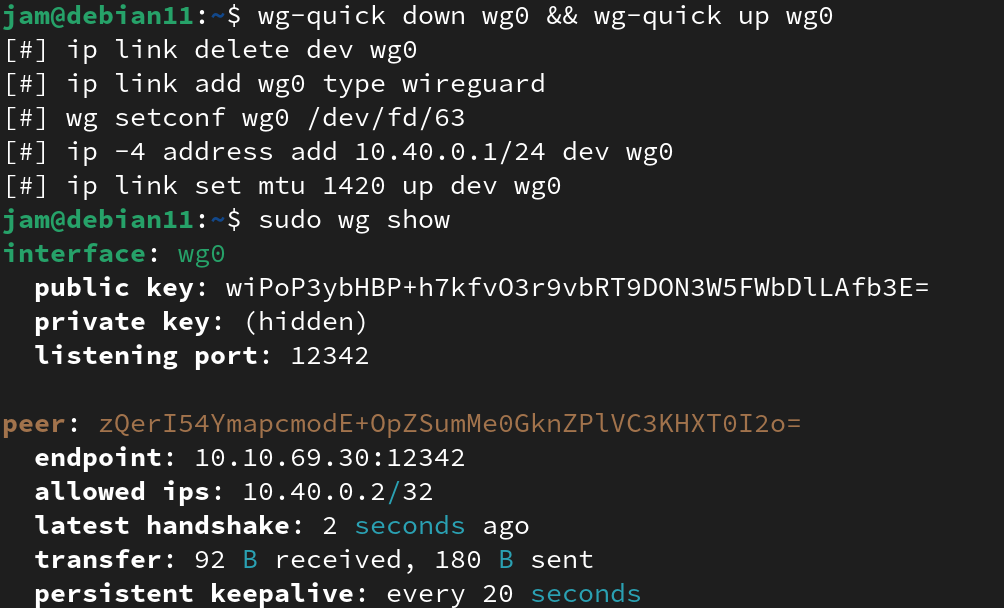

wg-quick down wg0 && wg-quick up wg0  Active Wireguard Tunnel! Just like that, we have a connection between the two hosts that is lightweight and encrypted. We can verify it by pinging one of the IP’s inside the tunnel:

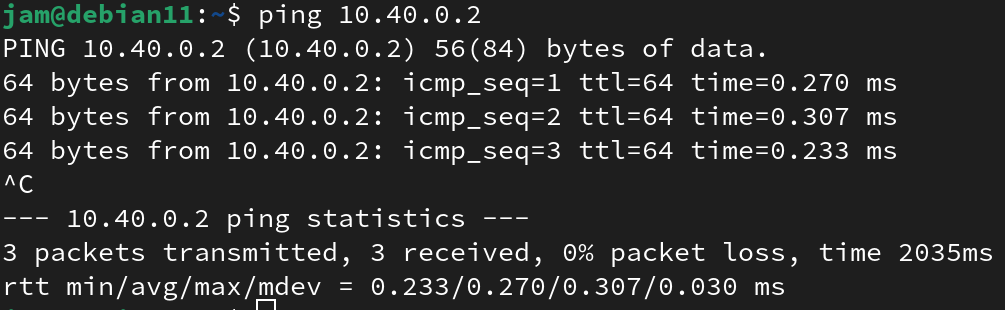

Active Wireguard Tunnel! Just like that, we have a connection between the two hosts that is lightweight and encrypted. We can verify it by pinging one of the IP’s inside the tunnel:  We can reach the endpoint’s IP —

We can reach the endpoint’s IP —

Securing SSH

Creating the tunnels between the Jumper and the endpoint is only part of the configuration. The other part of it is securing SSH on the endpoint. More specifically, putting in the line ListenAddress <ip>

This config option will make the OpenSSH server listen on the IP specified and no others. You can have multiple entries for this option for example if you want to add some redundancy to this setup.

There are also other options which may prove useful in the config. For example, disabling root SSH login or changing the port. Here is my list of options.

Debian: nano /etc/ssh/sshd_config

Rocky/RHEL: nano /var/lib/systemd/system/sshd.service

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

ListenAddress 192.168.174.11

ListenAddress 192.168.53.5

ListenAddress 10.40.0.2

Port 7184

PermitRootLogin no

PubkeyAuthentication yes

AuthorizedKeysFile .ssh/authorized_keys .ssh/authorized_keys2

PasswordAuthentication no

PermitEmptyPasswords no

ChallengeResponseAuthentication no

UsePAM no

X11Forwarding yes

AcceptEnv LANG LC_*

There are also other options you can do such as disabling TTY outright and forcing /sbin/nologin however I do not force this at the moment.

How to connect

Connecting to one of your boxes through the Jumper can be accomplished multiple ways. The easiest way is to store the SSH data in ~/.ssh/config. This file follows a specific syntax to outline hosts and other miscellaneous SSH details such as host names and port numbers. Alternatively, you can use arguments in the SSH command itself to dictate where to hop to and from.

SSH Config

The SSH config file can hold traits for each individual connection or wildcard traits. For example, if all your services use port 7184 for SSH, you could deploy this. I would advise reading the man page to learn more.

nano ~/.ssh/config

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Host Jump

User jumper

Hostname 192.168.53.1

Host Mail

User mail

Hostname 192.168.53.5

ProxyJump Jump

Host Mailbackup

User mail

Hostname 192.168.53.6

ProxyJump Jump

Host NS1

User dns

Hostname 192.168.53.7

ProxyJump Jump

Host *

Port 7184

After creating this file, you can connect to each host via typing:

ssh <name>

For example, connecting to my NS1 would be:

ssh NS1

SSH Parameters

If you do not want to create a manual configuration file, you can replicate this inline with the SSH command. Similar to the above, if you wanted to SSH to the NS1 server we would do the following:

ssh -J jumper@192.168.53.1 -p 7184 dns@192.168.53.7 -p 7184

The syntax of it of course being:

ssh -J <user>@<jumper_ip> <user>@<endpoint_vpn_ip>

Confirmation

After configuring this all, we can verify that not only is it going via the SSH tunnel but also that SSH is not listening on any public interfaces.

Going through the VPN

If we check /var/log/auth.log (or /var/log/secure on RHEL) we can see that SSH sessions have been established via our tunnel address, more specifically the jumper address:

Aug 17 21:07:16 hostname sshd[6296]: Accepted publickey for root from 192.168.53.1 port 1234 ssh2: RSA SHA256:ABCdefg...

Aug 17 15:07:46 hostname sshd[1343532]: Accepted publickey for root from 192.168.53.1 port 1234 ssh2: RSA SHA256:ABCdefg...

Another quick way to verify this is by using the w command:

1

2

3

21:11:12 up 6 days, 20:46, 3 users, load average: 0.00, 0.00, 0.00

USER TTY FROM LOGIN@ IDLE JCPU PCPU WHAT

dns pts/0 192.168.53.1 21:07 0.00s 0.00s 0.00s w

Verifying SSH only listens on the VPN address

There are multiple ways to see what net connections are active on a Linux host. The one I always remember is netstat -tulpn. Paired with a grep command, we can filter it to specifically show only the SSH service:

1

2

root@hostname:~# netstat -tulpn | grep 7184

tcp 0 0 10.40.0.2:7184 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 2448/sshd

As we can see in the above snippet, it is only binding to the address 10.40.0.2 as opposed to 0.0.0.0.